哈耶克:从理性经济人到仨自组织人

哈耶克:从理性经济人到仨自组织人

Hayek: From the Rational Economic Man to the Triple Self-Organizing Human

——从斯密“和平经济学”原点到共生经济学的思想桥梁

— The Intellectual Bridge from Adam Smith’s “Peaceconomics” to Symbionomics

钱 宏Archer Hong Qian

2025.10.28 · Singapore

一、战争、学习与觉悟

1914年,年仅十五岁的弗里德里希·冯·哈耶克(Friedrich A. von Hayek),因第一次世界大战的爆发,加入了奥匈帝国的野战炮兵团。他在意大利前线服役时,亲眼目睹了文明与秩序在战争中的崩解,也由此萌生了一个念头:理解人类社会如何在混乱之中仍能自发地形成秩序。

这成为他一生探求经济学与社会哲学的最初火种。1918年战后回国,他进入维也纳大学(University of Vienna)就读。起初,他对科学与哲学都怀有兴趣,曾深入研究恩斯特·马赫(Ernst Mach)的感知哲学,1919–1920年间专门研究人脑结构。随后,他转向法律(1920–1921),但司法考试一通过 ,他就投身经济学研究,成为奥地利学派代表人物弗里德里希·冯·维塞尔(Friedrich von Wieser)的学生。维塞尔推荐他进入路德维希·冯·米塞斯(Ludwig von Mises)主持的维也纳商会会计办公室工作,随即受命主持新成立的奥地利商业周期研究所(Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research)。

1923–1924年间,他赴美进修经济学课程,学习当时最前沿的时间序列经济统计方法。这次美国之行,为他后来对经济波动与知识分散问题的研究埋下伏笔。1930年代,哈耶克等奥地利经济学派因对大萧条(The Great Depression)的分析——尤其是商业周期理论的阐释——在欧洲学界崭露头角。

时任伦敦经济学院经济系主任莱昂内尔·罗宾斯(Lionel Robbins)注意到他,邀请他于1931年赴伦敦讲学。那四场讲座经整理后出版为《价格与生产》(Prices and Production),一举奠定了他在英国经济学界的地位,并让他获聘为伦敦经济学院的图克经济科学与研究教授。

多年后,他回忆道:“从1931年到1937年,是经济学理论史上最令人兴奋的几年。那既是一个高峰,也是一段时代的尾声——一个崭新且完全不同的时期正在开始。”

这正是他思想转向的分水岭——他开始对经济学自身的学科边界产生深刻的怀疑。

二、从奥地利学派到苏格兰原点

1940年代,哈耶克在反思计划经济与自由市场争论的同时,开始了思想的“追溯之旅”:他从圣西门主义者(Saint-Simonians)与奥古斯特·孔德(Auguste Comte)一路追至约翰·斯图亚特·穆勒(John Stuart Mill)。甚至在1950年代,他重走了穆勒1854–1855年与妻子从意大利到希腊的旅行路线,并在途中完成了《自由秩序原理》(The Principles of a Liberal Order)的初稿。

但真正让哈耶克找回思想归宿的,是他在1960年代初重返英国教学和生活的经历,使他彻底转向了苏格兰传统——那一脉源自大卫·休谟(David Hume)与亚当·斯密(Adam Smith)的思想血脉。

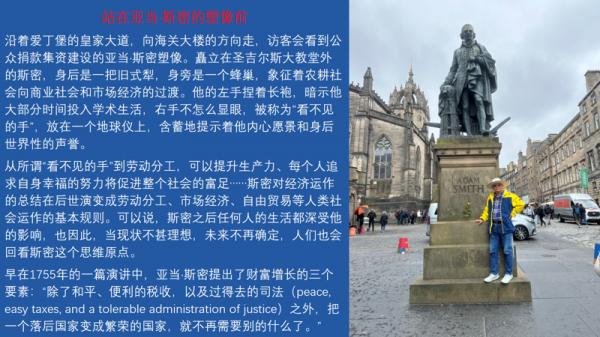

哈耶克从休谟那里继承了“社会演化”(Social Evolution)的非设计论思想,从斯密那里重新发现了“经济繁荣的原点”——早在1755年亚当·斯密在格拉斯哥发表的《论法律与政府的性质与原因》演讲中,他就提出了经济繁荣的三要素:

和平(Peace)、适当的税收(Moderate Taxation)、过得去的法律(Tolerable Justice)。

这比1759年的《道德情操论》(The Theory of Moral Sentiments)还早,是斯密思想的真正“源点”,他将“国富”(1776)建立在个人自由交换与信任的和平、社会分工与制度的和平、国际贸易与友谊的和平,以及法度的伦理基础上,而非功利性的简单生产与交易之上。

哈耶克深知这一点。他晚年的思想不再拘泥于市场理论,而是要回到斯密的“和平经济学”(Peaceconomics)原点,去探索:社会如何在自由的前提下实现秩序,在秩序的框架中保持自由——重新理解了经济学的本义——它不是财富分配的学问,而是和平、自由和信任的秩序学,是基于生命自组织连接动态平衡之交互主体共生的关系过程。

三、从经济预测到复杂秩序

当哈耶克意识到狭义的经济学理论,在30年代经历一个高峰和一段时期的尾声,也是一个崭新且完全不同的时期的开始时,他转向了政治哲学、法律、思想史和认知科学等多学科探索,为此,他甚至无意再与凯恩斯继续那场著名的辩论,即使是他最喜欢的熊彼得(Joseph Schumpeter),哈耶克也认为他没有自己连贯的哲学。正是这种特立独行的努力和对经济学的拓展,让哈耶克与主流经济学界显得格格不入,他甚至在他起家的伦敦经济学和迎接他的芝加哥大学,遭受经济学教授们的集体排斥!

哈耶克的核心突破,在于认识到经济学的真正任务不是预测,而是理解复杂性的现实生活——知识的局限、管理的边界、制度的约束。

这一转向,使他成为复杂性经济学、知识经济学与行为经济学的思想先驱。30年代中期后几十年,哈耶克主要研究政治哲学、法律、思想史、认知科学与经济学之间的关系,陆续发表了《通往奴役之路》、《经济学与知识》、《自由宪章》、《个人主义与经济秩序》、《致命的自负》、《知识在社会中的运用》、《竞争的含义》和《感觉的秩序》等影响深远的著作。

哈耶克认为,这些看似经济学之外的著作,是他对经济学理论做出的最有原创性的贡献,为什么?

四、仨自组织人:钱宏的解释

钱宏认为,因为哈耶克已经感到或发现:没有单纯的“理性经济人”,无论是市场经济还是计划经济,其主体都必然同时是经济自组织人、政治自组织人、文化自组织人三位一体的“仨自组织人”,即组织共生人,及其生命生命自组织连接动态平衡的交互主体共生关系。

所以,经济学并不是对经济做出预测,而必须涉及现实中的复杂现象(比如实际资产的具体运用过程及资源分配方式等自然秩序),如何处理知识、管理、制度的局限性而非做出具体的预测才是最关键的难题,亦即了解处于交互主体关系中的仨组织人(个体和共同体)综合政治、经济、文化行为,并给出准确的判断。

也就是说,哈耶克之所以伟大,在于他天才般发现了“理性经济人”假设的终结。现实世界的个体与共同体,从来不是单维的经济算计机器(无论是市场经济,还是政府经济),而是同时作为:三位一体的“仨自组织人”(Triple Self-Organizing Humans),即“组织共生人”:

经济自组织人(生产、交易、创新)

政治自组织人(选择、分配、治理)

文化自组织人(认同、信念、价值)

这正是共生经济学的思想起点:经济活动本质上是交互主体共生(Intersubjective Symbiosis)过程,而非纯理性优化过程。

五、哈耶克原创性体现在五个方面

一是超越理性经济人 —— 看到人的政治与文化维度,哈耶克不再将人视为只追求经济利益的理性个体,而是认识到人同时是经济、政治和文化活动的参与者,是一个多层面的“仨自组织人”;

二是聚焦复杂性而非预测 —— 预见了复杂系统科学,他认为经济学真正的难题不在于做出具体的预测,而在于如何理解和处理现实世界的复杂性,特别是知识、管理和制度的局限性。往前可以追溯到亚当斯密,往后可以联系到后世兴起的“复杂经济学”,以及2024年三位诺贝尔经济学奖得主的探索;

三是研究知识与秩序生成 —— 形成“知识的自发秩序”理论,他通过跨学科研究,探索了知识文化是如何在社会中传播、组织和应用的,以及市场经济如何通过非预设的自发秩序来运作;

四是强调自由的核心地位 —— 反对中央计划,维护社会多样性。他认为,只有在个人自由和社会规则得到保障的和平环境下,经济和社会才能持续发展,这使得他的研究与凯恩斯主义“干预经济”的观点产生了根本性分歧;

五是奠定新的研究范式 —— 连接经济学、政治学、法学与心理学,他对知识、制度、自由和自发秩序的深入研究,为经济学与其他社会科学(如政治学、法律、心理学等)的交叉研究奠定了基础,创造了一个新的研究范式。

总之,哈耶克之所以认为其“跨学科研究”极具经济学理论原创性,是因为他超越了单纯的“理性经济人”假设,认为经济活动的主体是同时兼具经济、政治和文化属性的“仨自组织人”(即组织共生人)。他发现,经济学无法仅凭预测来解决现实世界的复杂问题,更关键的是要研究知识、管理和制度的局限性,以及在个体和集体层面,如何处理个体和共同体作为“仨自组织人”的综合行为。

这一视角使他从主流经济学中脱颖而出,在政治哲学、法律、思想史和认知科学等领域转向中,最终创作出一系列影响深远的作品,成为继亚当·斯密之后经济学领域的另一座丰碑。

六、从哈耶克到共生经济学(Symbionomics)

哈耶克的理论在今天显得愈发重要。因为他揭示的不只是20世纪的经济学困境(当时在战争阴霾之下,“干预经济”成为包括法西斯德国、共产主义苏联和资本主义的美国在内的专家学者们,战前乃至战后的主导性共识,最终导致整个七十年代的世界性“经济滞胀”),也正是21世纪AI时代的核心悖论——如何在知识过剩、制度失孞、灵魂迷失之间,重建“自由、秩序与生命自组织连接”的动态平衡。

钱宏指出,哈耶克与亚当·斯密之间的思想通道,正是通往Symbionomics的桥梁:

“经济学的未来,不在预测,而在生命的自组织连接。”

共生经济学(Symbinomics)以“生产回归生活,生活呈现生态,生态激励生命”为核心逻辑,将斯密的“和平经济学”原点与哈耶克的“自发秩序”理论,置于“LIFE(生命形态)-AI(智能形态)-TRUST(组织形态)”三重交互关系之中,进而融入互联网、物联网、孞態网(MindsNetwork)三网叠加的基础生活实践,成为21世纪“和平经济学”的延续与重生。

七、堂吉诃德的隐喻

有人指出,哈耶克对于美国左翼知识分子有关“自由”概念之滥用的批评,如今不仅没有任何纠偏的迹象,反而越来越激进。所有这一切,事实上都和哈耶克当年的乐观想法背道而驰。

在西班牙古都托莱多(Toledo)的铸剑工坊,我驻足于堂吉诃德与桑丘·潘萨的组合雕像前,思绪回到了那一年。记得那时的电视上播放了一部连续动漫《堂吉诃德》,我大女儿才7岁。那段时光,她2岁时她妈妈前往天津读研究生,毕业后又去北京工作,她便与我在南昌相依为命,直到她6岁多才随母亲前往北京上小学。一天,我下班回家,看到她神情忧伤地对我说:“爸爸,堂吉诃德快死了!”这话让我既意外又触动——她的心里,是否无意间将我这个忙碌的父亲与那个执着于理想的骑士联系在了一起?于是,我轻声安慰道:“他死不了。”她却摇摇头,带着一丝焦虑说:“可是他生病了,今天是最后一集。”我笑了笑,坚定地回应:“就算他死了,他还会复活!”出乎意料,她冲我绽放出一个会心的笑容,那一刻,父女间的默契仿佛跨越了动漫与现实。

时过三十二,昨天我刚念初中的小女看到我在托莱多与堂吉诃德塑像的合影,又问了我一个问题:“老爸,唐吉诃德值得被颂扬吗?”我回复说:“他代表的是一种精神,你说呢?”她说:“在战场上明知道自己会输,因为对面过于强大也要往前冲也叫堂吉诃德精神?”“这是一种文学上的夸张表现手法,目的是突出骑士精神在极端不利的情况下能不能坚守到底,输赢只是一个表象。孩子,如果有空的话,老爸建议你看一下电影《勇敢的心》,主角华莱士就是一位为了自由而战,富有骑士精神的苏格兰英雄!”

当时与这尊雕像合影时,我心底升起一个感慨:“也许,这世界还需要骑士。”这一念头不仅是对堂吉诃德不屈精神的致敬,更是对人类在复杂时代中坚守理想的呼唤。

在这个意义上,把哈耶克比作“最后一个堂吉诃德”也未尝不可。但钱宏认为,哈耶克这位经济学领域最后的“堂吉诃德”,其丰功伟绩,正是我们当代人理解斯密“和平经济学”原点,和从这个原点再出发的Symbionomics之间的思想桥梁。

八、现实的回声

今天,当我们以这样的尺度去观察当下,与“政治正确”主流思想(包括多位诺贝尔经济学奖得主)显得格格不入的四个国家的人民选举出来的领导人——阿根廷总统米莱(Javier Milei)、美国总统川普(Donald Trump)、意大利总理梅洛尼(Giorgia Meloni),以及刚刚上任的日本首相高市早苗(Sanae Takaichi)——他们已经或正在推行的经济政策与外交努力,也许正能帮助我们超越左右、东西、官民的两极视野。

唯有如此,我们才可能以一种更平和、真实、接近常识的态度去善待之;以智慧、勇气与创造力,面对那被特权与失序所玩坏的全球化结构,重新定义并规范“LIFE(生命形态)—AI(智能形态)—TRUST(组织形态)”的三重关系——开启人类生活方式创新与再组织的臻美共生未来。

Hayek: From the Rational Economic Man to the Triple Self-Organizing Human

— The Intellectual Bridge from Adam Smith’s “Peaceconomics” to Symbionomics

Archer Hong Qian

October 28, 2025 · Singapore

I. War, Learning, and Awakening

In 1914, the fifteen-year-old Friedrich A. von Hayek joined the Austro-Hungarian field artillery as the First World War broke out. On the Italian front he personally witnessed the collapse of civilization and order amid war. Out of that shock arose a lifelong question: how does human society spontaneously generate order amid chaos?

That question became the first spark of his lifelong inquiry into economics and social philosophy. After returning home in 1918, Hayek entered the University of Vienna. At first, he was drawn equally to science and philosophy, studying Ernst Mach’s philosophy of perception and, between 1919 and 1920, researching brain structure. He then turned to law (1920–1921), but upon passing the judicial exam he immediately devoted himself to economics. He became a student of Friedrich von Wieser, a leading figure of the Austrian School, who soon recommended him to work under Ludwig von Mises at the Vienna Chamber of Commerce. There, Hayek was appointed to direct the newly established Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research.

Between 1923 and 1924, he went to the United States to study the latest techniques of time-series economic statistics — an experience that planted the seed for his later reflections on business cycles and the dispersion of knowledge. In the 1930s, Hayek and his Austrian School colleagues rose to prominence through their analysis of the Great Depression, especially their theory of business cycles.

At that time, Lionel Robbins, head of economics at the London School of Economics (LSE), invited Hayek to deliver a series of lectures in 1931. Those four lectures, later published as Prices and Production, instantly established his reputation in the British academic world and earned him the Tooke Professorship of Economic Science and Statistics at LSE.

Years later, he recalled:

“From 1931 to 1937 were the most exciting years in the history of economic theory. It was both a peak and an ending — the close of an era and the beginning of something entirely new.”

That moment marked a turning point. Hayek began to doubt the boundaries of economics as a discipline itself.

II. From the Austrian School to the Scottish Origin

In the 1940s, while reflecting on the debate between planned economy and free market, Hayek began an “intellectual return journey.” He traced ideas from the Saint-Simonians and Auguste Comte to John Stuart Mill. In the 1950s he even retraced Mill’s 1854–1855 journey with his wife from Italy to Greece, completing along the way a draft of The Principles of a Liberal Order.

But what truly restored his intellectual home was his renewed engagement with church and community life in early-1960s Britain. That experience turned him decisively toward the Scottish tradition — the intellectual lineage of David Hume and Adam Smith.

From Hume, Hayek inherited the non-design theory of social evolution; from Smith, he rediscovered the true origin of economic prosperity. As early as 1755, in his Lecture on the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, delivered in Glasgow, Adam Smith had already identified three foundations of prosperity:

Peace, Moderate Taxation, and Tolerable Justice.

This was four years before The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). It was Smith’s true point of departure: the “wealth of nations” (1776) was grounded not in utilitarian production or trade, but in a moral and institutional order of peace — peace in personal exchange and trust, peace in social division of labor and institutions, peace in international trade and friendship, all rooted in ethical law.

Hayek grasped this profoundly. In his later years he no longer confined himself to market theory. Instead, he sought to return to Smith’s original “Peaceconomics” — to explore how society can achieve order under freedom, and preserve freedom within order. He came to see that economics, in its true sense, is not a science of wealth distribution, but a study of peace, freedom, and trust — a relational order grounded in the dynamic balance of life’s self-organizing symbiosis.

III. From Economic Prediction to Complex Order

When Hayek realized that the theoretical economics of the 1930s had reached both its height and its exhaustion — marking the dawn of an entirely new age — he turned toward political philosophy, law, intellectual history, and cognitive science. He even lost interest in continuing his famous debate with John Maynard Keynes. Even of his admired friend Joseph Schumpeter, he said that Schumpeter lacked a coherent philosophy.

This independence and his expansion of economics beyond its traditional domain made him increasingly alienated from the mainstream. He faced open exclusion not only at the LSE where he had first risen to fame, but later at the University of Chicago, where many economists collectively resisted his appointment.

Hayek’s crucial breakthrough lay in realizing that the true task of economics is not prediction but comprehension — to understand the complexity of real life: the limits of knowledge, the boundaries of management, the constraints of institutions.

This intellectual shift made him a precursor of complexity economics, knowledge economics, and behavioral economics. From the mid-1930s onward, he explored the deep relations among political philosophy, law, thought, cognition, and economics, producing a body of influential works including The Road to Serfdom, Economics and Knowledge, The Constitution of Liberty, Individualism and Economic Order, The Fatal Conceit, The Use of Knowledge in Society, The Meaning of Competition, and The Sensory Order.

Hayek believed these works, though appearing to transcend economics, constituted his most original contributions to the discipline itself — and indeed, they were.

IV. The Triple Self-Organizing Human: Qian Hong’s Interpretation

According to Archer Hong Qian, Hayek had sensed — or discovered — that there is no such thing as a purely “rational economic man.” Whether in a market or a planned economy, every actor is simultaneously an economic, political, and cultural self-organizing being — a “Triple Self-Organizing Human,” or what Qian calls the Symbiotic Human.

Thus, economics is not about making predictions; it must address the real complexity of life — the concrete processes of asset use and resource allocation, the natural order of interaction, and above all, the limits of knowledge, management, and institutions. The essential task is to understand how individuals and communities, as inter-subjective symbiotic entities, integrate political, economic, and cultural behavior to sustain equilibrium.

In this sense, Hayek’s genius lay in intuitively declaring the end of the “rational economic man.”

Human beings and communities are not one-dimensional machines of calculation, but living entities that act simultaneously as:

Economic Self-Organizing Humans – production, exchange, and innovation

Political Self-Organizing Humans – choice, distribution, and governance

Cultural Self-Organizing Humans – identity, belief, and value

This triadic integration marks the conceptual origin of Symbionomics: economic activity is, in essence, an intersubjective symbiotic process, not a purely rational optimization.

V. The Five Dimensions of Hayek’s Originality

Beyond the Rational Economic Man — Hayek recognized the political and cultural dimensions of human beings, redefining humans as multifaceted “triple self-organizing” participants in economic, political, and cultural life.

Focusing on Complexity, Not Prediction — He foresaw the emergence of complexity science, arguing that economics must confront the limitations of knowledge, management, and institutions rather than pursue illusory forecasts — a lineage traceable back to Adam Smith and forward to 21st-century Nobel explorations.

Studying Knowledge and Order Formation — He articulated the “spontaneous order of knowledge,” investigating how cultural information propagates, organizes, and operates in society, and how markets function through self-generated, non-designed orders.

Upholding the Centrality of Freedom — Hayek opposed central planning and defended social diversity, maintaining that sustainable development requires a peaceful environment in which personal liberty and social rules coexist.

Establishing a Cross-Disciplinary Paradigm — By linking economics with politics, law, and psychology, he founded a new interdisciplinary framework that integrated knowledge, institutions, liberty, and spontaneous order.

Ultimately, Hayek’s originality lies in transcending the narrow hypothesis of the “rational economic man.” He saw economic activity as inherently tri-dimensional, involving the interplay of economy, politics, and culture. Through this, he redefined economics as a study of knowledge, limitation, and interaction, producing a corpus that stands as the second great milestone of economics after Adam Smith.

VI. From Hayek to Symbionomics

Hayek’s theory is even more relevant today. He revealed not only the intellectual dilemma of 20th-century economics — when “economic interventionism” became the near-universal consensus across fascist Germany, communist Russia, and capitalist America, ultimately leading to the stagflation of the 1970s — but also the core paradox of the 21st-century AI age: how to restore the dynamic balance between freedom, order, and life’s self-organizing connectivity amid knowledge overload, institutional decay, and spiritual disorientation.

Qian observes that the intellectual passage between Hayek and Smith forms the bridge to Symbionomics:

“The future of economics lies not in prediction, but in life’s self-organizing connection.”

Symbionomics rests on the triadic logic that production returns to life, life reveals ecology, and ecology inspires vitality.

It fuses Smith’s Peaceconomics and Hayek’s Spontaneous Order within the tri-axis of LIFE (biological form), AI (intelligent form), and TRUST (organizational form) — further integrated through the convergence of the Internet, Internet of Things, and MindsNetwork. In this way, it extends and revives the “Peaceconomics” of the 21st century.

VII. The Don Quixote Metaphor

Some have remarked that Hayek’s critique of the American Left’s abuse of “freedom” has gone not only unheeded but inverted — the ideological distortions he warned against have deepened. In that sense, he may rightly be called the last Don Quixote of economics.

Yet Qian contends that Hayek’s noble solitude — his unyielding defense of freedom and self-organizing order — makes him precisely the bridge through which our age can rediscover Smith’s Peaceconomics and move toward Symbionomics, the economics of symbiotic life.

VIII. The Echo of Reality

Today, when viewed through this lens, the four elected leaders who appear out of step with “politically correct” orthodoxy — Javier Milei of Argentina, Donald Trump of the United States, Giorgia Meloni of Italy, and Sanae Takaichi of Japan — may in fact be carrying forward Hayek’s unfinished intellectual legacy.

Their evolving policies and diplomatic efforts invite us to transcend the dualisms of left and right, East and West, government and citizen. Only then can we respond to the wreckage of globalization — once distorted by privilege and disorder — with calm, honesty, and common sense.

With wisdom, courage, and creativity, humanity may yet redefine and harmonize the triadic relationship of LIFE (bios), AI (intellectus), and TRUST (institutio) — thus opening the way toward a beautifully symbiotic future of renewed human life and re-organized civilization.